Come have a look at my website's new look: http://www.sharondolin.com.

I'll be blogging from there:http://www.sharondolin.com/category/blog/

Whirlwind

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Success Is All Smoke

Smoke is all there’s been in my life . . .

Success has got no taste or smell.

And when you get used to it,

it’s as if it didn’t exist.

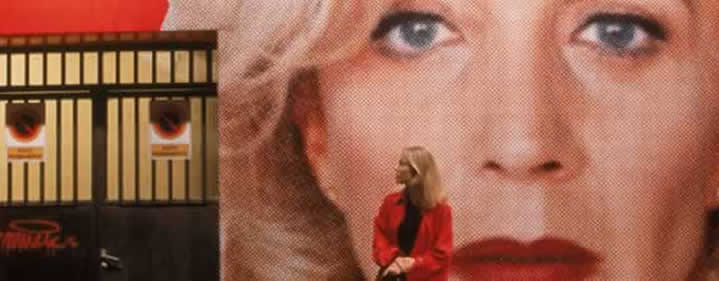

from Almodóvar’s All About My Mother

That’s what the successful older actor, Huma (fem. version of "smoke" in Spanish), says in the movie, which I recently re-watched. And I have to ponder it, here, in New York, which has got to be one of the most success-driven places on the planet. What counts as success for an artist? Getting to do the work you want to do and getting paid for it? Getting paid well for it? That might be an answer. Of course, we poets rarely get paid for anything. And yet we persist. Why do we do what we do? For glory? For the sheer joy of it? Someone, a new friend, recently asked me why I called such things as guilt, regret, indecision—all subjects of poems in my fourth book—vices. And I replied, It’s because they take me out of the moment—out of the present enjoyment of life. And that amounts to a certain kind of failure, I suppose. So perhaps I am at my most successful when I am most present: walking the dog in the morning and really breathing in the air, noting the season by the stage the trees are in, watching the sunlight filter through the branches. Or when I’m at my “desk,” which might be a subway car or a park bench or an actual desk—these days, the dining room table.

And yet I persist, as do so many others, in wishing for that other kind of success: the kind where people I don’t know know me. The kind where I get invited to give readings and talks for real money, knowing full well that to be a successful poet, in the deeper sense, may have little or nothing to do with such public strivings. As Christopher Hitchens wrote, paraphrasing Nadine Gordimer, “A serious person should try to write posthumously.” And for that, it is not necessary that anyone know me/you now.

Here's a quote I used to have over my desk. It's by another favorite artist of mine, Mark Twain, who said:

"Fame is a vapor, popularity an accident; the only earthly certainty is oblivion."

Yet I write this on the heels of a book party for Whirlwind, my fifth book (a number I find hard to fathom), and the publication of my new poems and Q&A featured in December’s Poetry. What is success? That I have persevered. That I keep challenging myself to write new kinds of poems. That I don’t care where the culture is moving. I still believe deeply in poems, in paintings, in music, in dance, in human connection. So as much as I toot my own kazoo like all the other New York—American—poets clamoring for some attention from a public that is mostly oblivious to poetry, I know that “All is vanity and a striving after wind.” But wind is all we’ve got. And some times, however briefly, it does have a piquant taste and even a sweet smell.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

A Force of Nature: Gerald Stern

That’s what I thought when I heard Gerald Stern, 87,

read from his two newly published collections (of poetry and prose) last night

at the Neue Galerie, the most elegant book party I have ever attended, hosted

by his wife, the poet Anne-Marie Macari. And it’s why I’m glad I’m not a tennis

player who has to retire at 32, or a dancer who might be lucky to dance till

s/he’s 45 (except for flamenco dancers, the true poets of dance, who draw down duende and can dance till they die).

And what a funny, yet apt place to toast this Jewish poet, while eating

spoonfuls of schnitzel. It reminded me of the way I feel, standing under the

Arch of Titus in Rome. We have survived. And Gerald

Stern reminds me once more (pace Frank O’Hara) why I’d rather be a poet.

“[C]ould I be the one / who carries the smell of dead birds

in his blood, and horses?” That’s how Gerry’s poem “Nietzsche” (which he read)

ends—a sentence that goes on for 12 lines, beginning with him walking through

“the Armstrong Tunnel” in Pittsburgh, I surmise, and then gathering momentum,

returning to the bleeding horse: “the snorting and the complex of / leather

straps,” that brings with it the grief over the dead with whom Gerry can no

longer talk (“Stanley” [Kunitz] and “Paul Goodman”), until that final image,

when Gerry becomes the human, all too human Nietzsche intervening and sobbing

over the flogging of the horse. Intervention, as Gerry said to us, which is all

we can hope to do.

Surely, that’s what Gerald Stern’s poems have done for me

and for so many other readers, students, fellow poets. He’s intervened in our lives with his hamish poetic voice (years ago with the dead skunk he has

to stop for in his poem “Behaving Like a Jew”) that is truly like Emerson’s

all-seeing eyeball with its sweep of history, of misery, of personal

friendship, of books that live and breathe for him. As generous and capacious

an imagination and person as you could ever hope to encounter. What a privilege

to be on the spinning globe with him.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

The Color of Ties / The Ties of Color

Red state is Republican, Blue state Democrat

|

| Blue-tied Romney sparring with red-tied Obama (photo from USA Today) |

A state is considered blue if the voting history trends to the

Democratic party and red if it trends towards the Republican party. These

colors are selected because they are on the opposite ends of the color

spectrum. In other countries, the color scheme is rversed, where red is the

color of the liberals and blue the conservatives. The exact use of this color

scheme emerged in the 2000 elections, due more to general agreement among

commentators than anything else.—Charlie

Red=Republican. Blue=Democrat.

There isn't any deep meaning. [my emphasis] It just

happened that way in the media broadcast of the 2000 presidential race. After

that, it became the accepted, albeit unofficial nomenclature of politics. As

Wikipedia describes it:

"Early on, the most common—though again, not

universal—color scheme was to use red for Democrats and blue for Republicans.

This was the color scheme employed by NBC—David

Brinkley famously referred to the 1984 map showing Reagan's

49-state landslide as a "sea of blue", but this color scheme was also

employed by most newsmagazines. CBS during this same period, however, used the

opposite scheme—blue for Democrats, red for Republicans. ...

"But in 2000, for the first time, all major electronic media

outlets used the same colors for each party: Red for Republicans, blue for

Democrats. Partly as a result of this near-universal color-coding, the terms Red

States and Blue States entered

popular usage in the weeks following the 2000 presidential election.

Additionally, the closeness of the disputed election kept the colored maps in

the public view for longer than usual, and red and blue thus became fixed in

the media and in many people's minds. [2] Journalists began to routinely

refer to "blue states" and "red states" even before the

2000 election was settled. After the results were final, journalists stuck with

the color scheme . . . . Thus red and blue became

fixed in the media and in many people's minds [3] despite the fact that no

"official" color choices had been made by the parties.

The quote goes on and on…

What I find interesting is the assertion that “there is no deep meaning” in it. But of course there is. Since the ‘Teens of the 20th century, the Red Party has been associated with the Communist Party. To be called a “Red” was the same as being called a Communist. And Communists, as we all know, are associated with the Left. And Democrats, though becoming more and more Centrist, began on the Left even if they’ve moved to the Middle.

So what’s going on here? It’s taken me years to adjust (and I still haven’t or hadn’t adjusted) to thinking of the Red Party as the Republican Party. Interestingly, this color code-switching nearly coincides with the demise and eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, one of the last bastions of so-called “Communism.”

Is there a deliberate emptying out of signified tied to the signifier of color?

With last night’s reversal: the Democrat sporting a bright red to go with the bright red carpet, the Republican sporting a royal blue tie to match the sky blue walls, I’m perplexed. Perhaps it was Obama unconsciously signaling to his constituents that he was still on the Left. And Romney signaling he was still the party of the rich. Their people must decide these things beforehand. Imagine if both came out wearing the same color tie. . .

The only thing constant was the two wives of the two candidates as well as the first woman commentator on PBS in luscious hot pink: pink being the color the most closely identified with women and femininity and sex. According to the InternetSlang dictionary, PINK means "Vagina."http://www.internetslang.com/PINK-meaning-definition.asp

Monday, October 15, 2012

What Is It About the Dodge Poetry Festival

Okay. It's pretty cool to read to a packed auditorium of poets and poetry lovers. To share the stage with so many luminaries like Natasha Trethewey, Terrance Hayes, Eavan Boland, Jane Hirshfield, and the inimitable Patricia Smith who took the photo below. To yatter on about poetry, my influences, going public with private feelings. To read from my new book and all my others. To sell books and sign them.

But what makes the Dodge special is the chance to change lives. Literally. I could feel that happening on Friday, the day devoted to high school students. I had finished up by early afternoon, was standing outside in the sun, when 4 young women sheepishly approached me. I recognized one of them. She'd been in the front row of the auditorium when I'd read earlier that morning. They came over to tell me how much my reading, my presence had meant to them, particularly when it came to reading certain poems. Now I had shied away from reading from my new book, Whirlwind, on that day, a book devoted largely to my divorce, though I must have read one poem from it at the end. Mostly, though, I read from early books, including my first book, Heart Work, which Sheep Meadow published way back in 1995. Now that I think about it, before any of these girls had been born. What moved and transformed them was my poem "If My Mother" about getting my schizophrenic mother to sign herself into a hospital. It made me realize all over again how difficult it is for individuals everywhere, particularly young people, to feel comfortable talking about such things. That there is still a stigma attached to mental illness, just as there is to alcohol and drug addiction. Perhaps even more so. One of them also was moved by "Passing" from Burn and Dodge, which talks about racial passing and my own experience of passing as Irish because of the way I look in combination with my Irish-sounding surname when I lived in Carroll Gardens in the late Eighties and early Nineties, when it felt unsafe to reveal myself in what was then a working class Italian neighborhood. I can sniff anti-Semitism the way I'm sure some folks can sniff racism.

The emphasis at the Festival was often on a more narrative or lyric confessionalism, for lack of better terms. I don't really recall anyone there from the more language-based or experimental sector of the poetry world. And while I'd argue that strict schools of poetry have pretty much gone away, there was a noticeable tendency to feature the popular, even populist poets. That's not to say they're facile. Far from it. Terrance Hayes read all new work every time I heard him and the poems were dizzying in their complexities. Dorianne Laux read a startling, brilliant new poem that jumped from Paul Simon and Grace and Graceland to the diamond mines in South Africa to those "diamonds on the soles of my shoes." And Jane Hirshfield always dazzles with poems that conjure the unsaid, the silences, as much as the said. But there was no Sharon Mesmer or Charles Bernstein or even Lyn Hejinian present.

It was thrilling, yet odd to get 6 minutes, really, to read to a packed house on Thursday night. And so I chose to read 2 poems, one from either end of the poetry spectrum: "Desire and the Lack"--as language-dense as possible--and "To the Furies Who Visited Me in the Basement of Duane Reade"--a poem of narrative hyperbole.

I do hope I get asked back.

But what makes the Dodge special is the chance to change lives. Literally. I could feel that happening on Friday, the day devoted to high school students. I had finished up by early afternoon, was standing outside in the sun, when 4 young women sheepishly approached me. I recognized one of them. She'd been in the front row of the auditorium when I'd read earlier that morning. They came over to tell me how much my reading, my presence had meant to them, particularly when it came to reading certain poems. Now I had shied away from reading from my new book, Whirlwind, on that day, a book devoted largely to my divorce, though I must have read one poem from it at the end. Mostly, though, I read from early books, including my first book, Heart Work, which Sheep Meadow published way back in 1995. Now that I think about it, before any of these girls had been born. What moved and transformed them was my poem "If My Mother" about getting my schizophrenic mother to sign herself into a hospital. It made me realize all over again how difficult it is for individuals everywhere, particularly young people, to feel comfortable talking about such things. That there is still a stigma attached to mental illness, just as there is to alcohol and drug addiction. Perhaps even more so. One of them also was moved by "Passing" from Burn and Dodge, which talks about racial passing and my own experience of passing as Irish because of the way I look in combination with my Irish-sounding surname when I lived in Carroll Gardens in the late Eighties and early Nineties, when it felt unsafe to reveal myself in what was then a working class Italian neighborhood. I can sniff anti-Semitism the way I'm sure some folks can sniff racism.

The emphasis at the Festival was often on a more narrative or lyric confessionalism, for lack of better terms. I don't really recall anyone there from the more language-based or experimental sector of the poetry world. And while I'd argue that strict schools of poetry have pretty much gone away, there was a noticeable tendency to feature the popular, even populist poets. That's not to say they're facile. Far from it. Terrance Hayes read all new work every time I heard him and the poems were dizzying in their complexities. Dorianne Laux read a startling, brilliant new poem that jumped from Paul Simon and Grace and Graceland to the diamond mines in South Africa to those "diamonds on the soles of my shoes." And Jane Hirshfield always dazzles with poems that conjure the unsaid, the silences, as much as the said. But there was no Sharon Mesmer or Charles Bernstein or even Lyn Hejinian present.

It was thrilling, yet odd to get 6 minutes, really, to read to a packed house on Thursday night. And so I chose to read 2 poems, one from either end of the poetry spectrum: "Desire and the Lack"--as language-dense as possible--and "To the Furies Who Visited Me in the Basement of Duane Reade"--a poem of narrative hyperbole.

I do hope I get asked back.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Poetry of the Shofar / The Shofar of Poetry

After a long hiatus, I'm back, to post on Whirlwind, my blog about poetry, the arts, and whatever else passes through me.

Each year, Jews the world over listen to one of the crudest of instruments. In the midst of abundant prayers, we people of the book, the word, the Torah, the ones who value interpretation of what is written, listen to the orchestrated blasts of a ram’s horn. It strikes me as a paradox, though quite poetic, to do so. It is a mitzvah to hear the shofar being blown. It’s also a commandment. And yet. The shofar blast is the place beyond words, beyond meaning we can articulate, beyond time. Did the shofar blow at the moment of Creation, which is what we are celebrating every year? Did the Jews in the desert hear the shofar when Moses communed with God on Mount Sinai? I don’t know. But I do know that there is something in us, verbal as we Jews certainly are, that yearns for what lies beyond words. What even words can’t say. And so we turn to the animal. The ram. Sign of the akedah: the binding of Isaac by his father Abraham, a story we read from the Torah on the second day of Rosh Hashanah. Sign of the prohibition against child sacrifice. Sign of the mystery. Sign, perhaps, of the wound in creation. The sound of suffering. The sound of liberation

[The photo, by the way, is of Antelope Canyon, in Arizona.

Each year, Jews the world over listen to one of the crudest of instruments. In the midst of abundant prayers, we people of the book, the word, the Torah, the ones who value interpretation of what is written, listen to the orchestrated blasts of a ram’s horn. It strikes me as a paradox, though quite poetic, to do so. It is a mitzvah to hear the shofar being blown. It’s also a commandment. And yet. The shofar blast is the place beyond words, beyond meaning we can articulate, beyond time. Did the shofar blow at the moment of Creation, which is what we are celebrating every year? Did the Jews in the desert hear the shofar when Moses communed with God on Mount Sinai? I don’t know. But I do know that there is something in us, verbal as we Jews certainly are, that yearns for what lies beyond words. What even words can’t say. And so we turn to the animal. The ram. Sign of the akedah: the binding of Isaac by his father Abraham, a story we read from the Torah on the second day of Rosh Hashanah. Sign of the prohibition against child sacrifice. Sign of the mystery. Sign, perhaps, of the wound in creation. The sound of suffering. The sound of liberation

[The photo, by the way, is of Antelope Canyon, in Arizona.

It's how I picture the inside of a shofar.]

For me, the shofar is like poetry. We go to poetry to be

moved. To hear language that is encantatory, even revelatory. Metaphors and

images that leap in ways that are not entirely rational. But surrounding every

poem, each line of verse, is the white space: the shofar of silence that

punctuates the sound of words and phrases. Silence we feel more deeply because

the words all point to the ineffable. If poems are prayers, then the shofar is

the space in between our prayers. The shofar of space. The shofar of time.

We think that we, as humans, are given something that the

animals are not given. But it is only humans who need the gift. The animals

already embody it. Thus we take up the shofar and blow: Tekiah, Teruah,

Shevarim . . . blasts, toots, wails, blares, laments.

I go to synagogue each fall to pray: to recite the words in

melodies my ancestors sang but also to stop and hear what lies beyond the

limits of speech. What points to the void. Or the transcendent one. The shofar.

A footnote: Tonight I went to hear a program honoring John

Cage at 100. It was an alternation, a dialogue, of music between Cage and

Pierre Boulez. It was the first time I had heard Cage’s 4’33” (1960) performed. It is 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence. Well, there is never

complete silence. Just the instruments and musicians were still as was the

conductor. Perfectly still. But the sounds, the clicks, the paper rustlings,

throat-clearings, all the ambient noise in the audience at Columbia

University’s Miller Theater, where I was, including all the buzzing in my head,

as in everyone else’s heads, I suppose, continued. This, too, was a shofar of

silence.

Labels:

akedah,

Jews,

John Cage,

Mount Sinai,

poetry,

Rosh Hashanah,

shofar,

silence

Friday, July 20, 2012

Blogging for Best American Poetry

I'll be blogging for Best American Poetry while I'm in France for the next few weeks, so catch me there:

http://thebestamericanpoetry.typepad.com/the_best_american_poetry/

http://thebestamericanpoetry.typepad.com/the_best_american_poetry/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)